- Home

- Jennifer Knapp

Facing the Music Page 10

Facing the Music Read online

Page 10

Shine on me!

Once a slave to sin but now Your blood has set me free!

If there’s anything that I can do Lord, anything that I can say-

Anything that I can do to make you my way-

Then let it be . . . !

—“Shine,” Circle Back

It wasn’t that I was necessarily offended by the idea of faith-based music. I just wanted to reach for the kind of musical and poetic depth that I had come to admire as a listener. For all my years as a trumpeter, playing High Church music, I had no problem leaning into music that pointed toward the heavens. It was just that, when it came to music, I wanted to get lost in lyrics that were rich and deep with meaning. Even when it came to my choice in popular artists, I had never been a pop-radio junkie. I loved songwriters like Natalie Merchant and Joni Mitchell, whose poetry had a way of mysteriously connecting my earthbound soul with their divine muse.

I continued to be fascinated that I, of all people, had had an experience with faith so radical that it had altered my outlook on life. My life had literally been saved, but it sounds so cliché to me (even still) to say that Jesus saved me, when there is so much more to the story. My choice to be a Christian was important, so I didn’t want to be trivial in my writing. I wanted to try to tell the truth of my new spiritual life and set it free to show up in the lyrics.

All the pennies I’ve wasted in my wishing well

I have thrown like stones to the sea.

I’ve cast my lots, dropped my guard, searched aimlessly

For a faith to be faithful to me.

—“Faithful to Me,” Kansas/Wishing Well

It was all well and good to say that Jesus had saved me, but so too had a good therapist and some serious cognitive therapy. With my new pursuit as a psychology major, I wanted to explore more about how the human psyche develops and functions.

I was fascinated by how, even in secular, academic conversations, there always seemed to be a roving dialogue among the students about what is or isn’t supposedly normal. To me, it was similar to the attitude that I encountered in the church, when we discussed whether who/what was or wasn’t good.

On any given Sunday, I’d find myself immersed in a church culture obsessed with how imperfect or lacking we are as human spirits. The conversations always seemed to center around how broken humanity is, how distant from the perfection of Christ we all are, and how laborious and frightening it can be to continue to aspire to the seemingly unattainable sinlessness required of the Christian disciple. At times it left me wondering why I even bothered imagining that I could renew my life if all I could ever be was one misstep away from spiritual disaster.

On Monday morning, perhaps in a psychology of adjustment class, I would find myself confronted with how inescapable most human behavior actually is. None of us are immune from precariously trying to balance our primal and cognitive needs. We have sex drives and hunger, greed and compassion. Strangely, along the way we usually manage to mix our own experiences with shame and insecurity that threaten to overpower our sense of emotional well-being. If we’re lucky, we will discover what it is within us that helps us press on.

Creatively, as a writer, and a person of faith, I became fascinated with human frailty. How do we cause it, respond to it, or endure it? I saw benefits in both psychology and faith. Between the rational and spiritual, I felt like I was finding my peaceable footing with my own peculiarities. In my own life, I was eager to move beyond the Christian idea of flawed humanity and get on with living life to the full. If we are what we are—that is, inescapably human—then part of my responsibility is to learn how to honor myself and others along the way. From a Christian perspective, if Christ’s sacrifice was to represent how my sinful nature (read: human nature) is reconciled with God’s perfect holiness, then why should I be afraid to acknowledge my true self?

I was free to be loved for who I was and wanted to live that way. I didn’t want to live under a cloud of shame for being, as it turns out, only human. The best of what Christianity would ever teach me was that even on my darkest days, no matter what condition I was in, I was a person made to be loved. As a child, there were times when I never dreamed this could have possibly been true, but all that was changing for me.

There’s a place in the darkness that I used to cling to

That presses harsh hope against time.

In the absence of martyrs there’s a presence of thieves

Who only want to rob you blind.

They steal away any sense of peace.

Tho’ I’m a king I’m a king on my knees.

And I know they are wrong when they say I am strong

As the darkness covers me.

So turn on the light and reveal all the glory.

I am not afraid.

To bear all my weakness, knowing in meekness,

I have a kingdom to gain.

Where there is peace and love in the light

In the light, I am not afraid

To let your light shine bright in my life, in my life

—“Martyrs & Thieves,” Kansas

THE LYRICS STARTED taking the tone of self-examination and discovery, but I had yet to find a place where I could do so with abandon. Most of the work I found in the summertime was at youth camps or Sunday evening services, where I was expected to be bright and cheery, wholesome entertainment for the kids. When I launched into a pulsing, dramatic tune, singing “You in the mirror, staring back at me . . . Oh, conscience let me be,” the children seemed bored and the pastors looked concerned.

For one thing, I didn’t really look like the so-called good Christian girl most people were expecting. I usually dressed in jeans, some kind of T-shirt, and a pair of boots. It was a far cry from what most of the churchgoers expected to see.

Girls were supposed to wear dresses to church, play piano, and sing politely.

Me? I was pounding out rock songs on a guitar, sweating, breaking strings, and generally more than eager to talk about how hard it was to measure up to the high standards of Christian living. Usually, the soundtrack for elementary Sunday school was more genteel. Most folks were happy to support my love of music because I was singing about my faith, but weren’t always in agreement that the church sanctuary was the best place for it.

Fortunately for musicians like me, Christian culture had embraced the idea of the live music coffeehouse. By the late 1990s, Kansas City was teeming with them. Whether it was a makeshift venue set up in the basement of a church or a strip-mall bookstore converted into a barista parlor for the night, there were finally places a good Christian kid could go to hear some music that expressed their own spiritual experience, rather than simply parroting the faith that they had inherited from their parents. It was a great environment for college students seeking an alternative to the alcohol-fueled club scene to have some good clean fun, but it also proved to be a safe place for many of us to explore and live out our own ideas about faith without the worry of upsetting the applecart of orthodoxy.

On the weekends, when I wasn’t working in a church somewhere, I drove up from Pittsburg to Kansas City so I could hang out at my favorite venue, New Earth Coffeehouse. Hearing the kind of music that was being played there and chatting with different kinds of people, altered everything I thought I knew about what Christians were supposed to look and sound like. Preppies, virgins, druggies, Baptists, Pentecostals, skeptics, rich, poor—it didn’t matter. We came. Hundreds were packed in like sardines and got lost in the sounds of artists like Dakoda Motor Company, Over The Rhine, Waterdeep, Dime Store Prophets, and Sixpence None the Richer. There were many nights when I stood, pressed in among the crowd, and wondered if I would ever be cool enough, potent, or talented enough to play there.

The sounds and the lyrics that came from those musicians blew my mind. Their music and personalities seemed subversive compared to the light of

the sanctuary. Heavily tattooed young men took the stage, cranked up their amps, and let it rip. Solo acoustic guitarists sat center stage and bared their souls so freely that we were compelled into reverent silence.

The artists that left us speechless were those that dared listeners and performers alike to be brave and honest about their true selves. Ska bands, rock bands, songwriters, and poets—all of them young and set free on the stage to tell the story of their journeys. It was different because they shared about their experience as Christians, the good and the bad, the believers and the cynics alike without fear of judgment against their imperfections. A wide path was given to all to explore and stumble, if need be, toward a spiritual experience that called and united us. We just were, and the art we shared was what came out of it.

I will never forget the first time I got a chance to play at New Earth. It might as well have been Carnegie Hall, such was the level of admiration for all I had seen and heard there. Before I had been one of the many silhouetted heads floating behind the spotlights, clapping and hungry for inspiration. Now, I was the one, exposed and center-stage, being called upon for greatness.

I had a half-hour set to fill and perhaps only four songs in which I had any confidence. My knees shook like jelly. My hands cramped and sweated. Just me and my guitar, left alone in a room full of people who had never heard of me. Madness.

I don’t remember playing the songs as much as I remember the rapid-fire thoughts that shot through my mind while I played.

Don’t screw it up.

What am I doing here? How did I get myself into this mess?

Wow, this is so awesome! I’m killing it . . .! Oops.

This song is so cheesy; they hate it. I gotta write something better.

Is that an espresso? Man, I’d love an espresso right now.

Do they really like my songs that much or are they glad I’m finally finished. Is that good applause or bad? Oh, my God, what have I done? Thank God this is over.

My first gig there was a crucible of sorts. Resident pastor and founder of the little urban church/coffeehouse, Sheldon Kallevig, said I could give it a go but, in the end, it was the room that decided.

“There are no promises here. If they like you, you come back. If they don’t, well . . .” He was candid, yet openhearted about it. He had the spirit of a man who wanted every contributor to succeed, but success wasn’t necessarily about popularity at New Earth. The folks who came back tended to be those who tapped into the journeyman spirit of the community that was there. You could play any style you wanted to, talk as much or as little about Jesus as you needed, be holy or even a little unholy, but you had to come with an eye to love and making a way for others. Those coming to simply make a name for themselves or who just played for the sake of praise didn’t seem to last long. At New Earth, you had to find a way to connect on an emotional level.

Through the blur of my first night, I must have done something right, because I ended up cutting my teeth in that coffeehouse. I think I played my first set there in 1994, and watched countless other artists perform, grow, fail, and succeed along the way. By 1996, I was in among them—an artist in my own right, headlining a few nights a year at New Earth and making fans that were urging me to continue.

eleven

Long before the Internet became the workhorse of the modern musician I was amassing a humble following. There was no digital social network. I didn’t have a Web site. It was all about doing gigs, word of mouth, and miles of open road. And it was more than helpful if you had a CD.

The little Circle Back cassette tape Byron and I made did well for a while, but I was writing more music, outgrowing my older work, and gaining more regional fans familiar enough with me that they wanted to hear my latest work in the modern CD format. In between college classes and touring, Byron sat me down in the studio and helped me arrange and record my songs into a full-length project, titled Wishing Well.

Recording your music means that your songs can go to places you’ve never been. Besides selling CDs at shows, you can pop them in the mail and send them to a deejay, to a college events planner, or even to a record label in hopes that someone will actually listen to it, like it, then offer you a deal that will change your life. I didn’t know it, but Wishing Well would be a project that would change my life.

Over the course of a year I had sold over three thousand copies of that CD. During my fourth year of college, Byron sent CDs to every Christian label in the market. He’d even managed to get a couple of well-known trade magazines to write reviews of my indie work.

From the early days of Captured, Byron had always had an unshakeable belief that I had what it takes to be a legitimate artist. I had been traveling along with the idea, enjoying getting to play, and loving that I was paying my bills doing something that I loved to do, but I figured the odds of making a lifelong career of it were long. However, by the spring of 1996, Byron started to get calls from Nashville.

For a while, it seemed as though Byron was fielding a steady stream of phone calls from CCM (contemporary Christian music) producers and A&R representatives. I didn’t even know what an A&R guy was until Byron explained to me that it was short for artists and repertoire. (Those are the record company personnel in charge of discovering and signing new talent, along with managing the current roster of artists on the label.)

But, for all the phone calls, it didn’t seem that I was what the big labels were looking for. There were only a few guitar-wielding chicks that I had ever heard of in CCM anyway, and I didn’t look or sound anything like them. I was used to playing in grungy little Christian coffeehouses for college students. When I heard artists like Amy Grant, Twila Paris, and Sandi Patty, I thought there was no way that CCM would consider me. They seemed so clean cut. Me? I was a woman who grew up in the world. I had a dark past littered with sex and booze. I had a hard time imagining, despite my story of redemption, that I had been a Christian long enough to be considered trustworthy enough to be on a Christian label. I held out a little hope when I got hold of artists like Margaret Becker, Ashley Cleveland, or even Christine Dente of Out of the Gray. They wrote and sang like they’d actually lived out a few hard, unholy years in their lives, but had they really? Anyway, who was I compared to them? They all seemed so shiny, spiritually certain and . . . wearing dresses!

At times, I could be crass and unpolished with my onstage delivery, enough that some people wondered if I was polite enough to have a career that relied on a predominantly conservative church audience.

I remember one day, when I was sound checking at a church before a concert, one of the fellows running the PA system came over to give me a hand in setting up.

He’d heard me described as a rock-and-roll chick, but was confused when I showed up with just my guitar.

“You got a band? Where’s your band?” he asked, looking me and my guitar up and down as if we were somehow unprepared.

“Nope. It’s just me.”

“Tracks? What about tracks then? Don’t you have any cassette background tracks you’re going to use? I gotta tape player wired to the system,” he offered, still baffled.

“Nope. It’s just me.” I tried to keep my growing agitation to a minimum.

“Well, then, wha . . .who . . .?” Exasperated, he kept looking at me as if mystified at how I was to perform with no band and no backing tracks and only a guitar. I felt like I clearly wasn’t the sweet little singing Christian girl he needed me to be. “Who do you play with then?”

I replied, “I play with myself.” I giggled aloud at what I had insinuated, but he didn’t seem to notice. Again, for my own pleasure and to see if he would cotton on. “Yep. I play with myself.”

The young sound guy turned beet red and walked away, and that was the end of our preproduction conversation.

I could get away with that kind of thing in the underground scene, or at some out-of-the-way church somewher

e, but on a CCM label?

Byron got quite a few calls, but I never seemed to make it past the initial phone call. Well-respected labels like Sparrow, Ardent, and Forefront came and went in a flash, and I started to figure that was pretty much the lay of the land. I’d have my fun traveling around for a few years while I finished school, but that would pretty much be the end of it. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

At around that time, a group called DC Talk was revolutionizing the face of CCM rock music with their double-platinum, Grammy-winning album “Jesus Freak.” To say this album was a game-changer in the world of Christian music is an understatement. They eclipsed the CCM marketplace and spilled out into the mainstream world. Christian kids were flipping out. Almost overnight, DC Talk made being a young Christian a cool thing. Teenagers and young adults finally had a soundtrack that helped legitimize their Christian cultural experience. Every track on that album channeled the rumbling teenage angst of the late nineties, familiar to fans of Nirvana, Stone Temple Pilots, and Pearl Jam. The dark, warm, electric throbbing manifested itself at live concerts, where, at last, a hormonally raging Christian kid could cut loose and mosh his brains out. For nearly a decade, the wave of DC Talk’s “Jesus Freak” took the social stigma out of being Christian.

The driving force behind DC Talk’s vision was Toby McKeehan. Toby was one of the trio of front men for the group. Toby not only had a vision for what he hoped DC Talk could accomplish, but expanded his vision by starting his own label, Gotee Records. Their early roster included a wide variety of acts. Among their early notable groups were R&B trio Out of Eden, grunge-rockers Johnny Q. Public, and the hip-hop duo GRITS.

They were a small company, with little staff and less money, but they were determined to offer music from Christian artists that reflected more of the faith culture than just middle-class, conservative, white folks who had grown up in the church. Toby and his crew had a heart for real people who had been through real life and wanted to offer more than clichéd music.

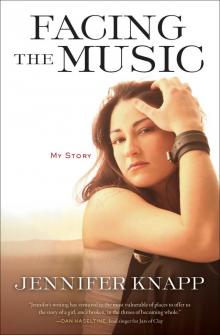

Facing the Music

Facing the Music