- Home

- Jennifer Knapp

Facing the Music Page 5

Facing the Music Read online

Page 5

I don’t think he understood my dream of wanting to become a skilled musician or how much his support as a father mattered to me.

Eventually, we struck a kind of deal. My parents would give me use of one of their old cars, keeping it insured and registered. In turn, I would do whatever it took to keep it running. That meant earning my own gas money, keeping up my good grades, and generally staying out of trouble.

“You can help around the house by chipping in with the bills. Pay for what you can. School books, music paper, gas money, movies—whatever,” my dad said. “If you want it, you’ll need to be able to afford it. Then . . .” he paused. “Well, that will help us save up for college.”

“Done deal!” I took my oath and ran with it. I found part-time jobs that fit my busy school life and help to fund my passions. Whenever I felt the grind of not wanting to clock in for work or got bored with my school work, I reminded myself of the future.

I acted as if there were not a minute to be wasted. If I wasn’t busy serving up egg rolls at the local Chinese restaurant, I was delivering pizza. When I wasn’t at work, I was usually in a rehearsal, a lesson, or performing. It was even better when I was performing and working at the same time.

In the summer, I found work playing Haydn concertos at weddings. In the Advent season, the organist for the local Methodist church put me to work with all manner of challenging cantatas. I was even asked to be on call as a trumpeter for funerals at the local VFW. When the last report of the twenty-one-gun salute had fired, it fell to me to complete the honor by playing “Taps.” Playing at the funerals was strange at first. I didn’t know how to react while others mourned the passing of their loved one, but eventually found a kind of peace in offering the gift of music.

So much of my performance work in the community was happening in sacred spaces. All that time, being a part of and witnessing the spiritual impact of music during the weddings, funerals, and High Church ceremonies filled me with a growing sense of reverence for Divinity. I recognized the hope’s longing that filled the hymns’ refrains. I wasn’t thrilled with the idea of religion, but I couldn’t help but be moved by what seemed a distant, faint voice of comfort. Inside my chest, music and spirituality seemed to be made of the same stuff—as if sounding in the same voice. There were times when it felt like I was being called to. By who or what, I couldn’t say, and didn’t want to say. The idea of calling that sensation by a name—to call it “God” aloud to others—was too provocative for me, but it didn’t keep my spirit from drifting into it. From time to time, I became aware that my imagination had wandered off into some kind of reassuring conversation with a distant being. I suppose some folks would have called it prayer. Part of me wanted to say that I believed in God because that’s what good girls do, but my growing pride and sense of personal accomplishment was such that I wanted to push aside such notions. That business might have been necessary for some, but I felt I was managing just fine without it.

The truth was that I wasn’t doing fine. I was slipping.

For four long years, I had kept my eyes on the prize of college. By my senior year, I was counting down the days until graduation. I had successfully auditioned for, and was granted, a scholarship at nearby Pittsburg State. PSU was a good back-up plan, but I wanted to follow in the footsteps of my mentor, Carol. The University of Kansas (KU), in Lawrence, was her alma mater and was the school that I had spent my days dreaming about. Every day, I would race to the end of our country driveway to check the mailbox for the letter that would confirm their great desire to have me as an undergrad. KU’s tuition was pricey compared to Pitt State, but I had the confidence that I had the grades and musical pedigree to warrant enough scholarship money to supplement what modest income my father had promised to put toward my goal. For four years running, I was first-chair trumpet for the Kansas All-State Band. I had numerous State medals to my name in multiple disciplines and, clearly, enough ego to get me there.

I waited and waited, but the letter I had hoped for never came. Many of my peers had already decided and confirmed where they were going to school next, but I was still on the bubble. It had never occurred to me to actually go up to the KU campus and audition as I had for PSU. The fact that I had auditioned for Pittsburg was actually an accident. I happened to find myself on campus for a State competition hosted by PSU. I was there anyway, so I figured it wouldn’t hurt to go through the motions. Little did I know how fortuitous that audition would be.

In truth, though I had dreamed of college, now that it was time to start making it happen, I was finding it difficult to figure out how to proceed on my own. In the infrequent and brief conversations I had had with my father about the matter, we spoke little more about it than we did our previous financial arrangement. I had honored my end of the bargain, but eventually it became clear that our agreement would not come to fruition as I had imagined it.

One day, not long into my senior year of high school, I came home and noticed a new horse in the paddock. The gelding was easily admired. Courtly, muscular, and immaculately groomed, he was the most beautiful horse that had ever set foot on our farm. This animal wasn’t cheap and I knew it.

In that instant, I was crushed. I realized that there was no family plan for my future. It had all gone into the horse.

I held out hope that the steed belonged to someone else and that we were boarding it, maybe even training it for a season. But when I confronted my father about it, my worst fears were realized.

“What’s with the new horse?” I tried to play down my internal panic while watching my dreams slip away.

Coolly, my father replied, “It’s your stepmother’s new horse.” He paused, filling the gap with defeated silence. He took yet another beat and then: “She bought it.”

“Seriously?” I asked with teenage sarcasm. I felt my body release all the chemicals of despair and rage into my bloodstream like a hot intravenous drip.

“How much? How much did you guys pay for that thing?”

It was unlike me to be so forward and prying into our family finances, but I wanted to know. He had promised me college support, but he and I both knew we weren’t a family of great enough means to afford both. I wanted his confession.

“Fifteen thousand dollars, ” he said flatly, then walked away.

I came unhinged. All the energy that fired its way through my body shuddered with a violence that felt sure to rip me apart. Overcome by panic, my body began to contort and twitch against my control. I rocked back and forth, grasping at my chest. My vision went black. I couldn’t see, but I could hear my breath and a groan that seemed to come from a distant place, apart from me.

When the color began creeping back into the world, a thousand little voices came with it. A decade’s worth of family quarrels replayed and echoed through my head. Every insult I had ever heard joined in chorus. Every insecurity that I had ever carried inside my little heart spoke at once. Every dark and evil voice that loved to come in moments like this confirmed I was what I had always feared . . . nothing. They all swirled about in a buzzing fury until I finally channeled them all into one meaning. One sentence to describe the absolute heartache I felt at that moment.

“He chose her,” I said aloud. Calm now, and detached. It took a decade for me to see it, but it finally sunk in. My father had made his family, and though I was there to witness it, ultimately, I had not been grafted in. I just didn’t see until that moment. I had been too focused on my own life, burying my head in music and dreaming, but, now, I couldn’t ignore it any more.

My father and stepmother had two sons by now. I had two brothers, but I hardly knew them. I watched them grow in my stepmother’s belly like an apparition that became manifest in our world, but I never dared to touch them. So distant had my stepmother and I become, the only serenity my family ever seemed to have was when I was separated, locked in my room, or busy with my own affairs. I felt that they did not n

eed me. They did not want me. And, worst of all, it seemed that I would never be missed.

Over the last decade, my parents had built their family, but that day I understood that neither I nor my sister had truly been a part of it. It was as if we were appendages or acquaintances, rather than children. We were the remnants of my father’s previous life, not the evidences of his current one. I began to see it all play back as if it were a movie, but the role I held in it began to evaporate. It was like when my sister moved away. Her person was literally forgotten. Her pictures removed. Her name left unspoken. I realized that she had been erased upon her departure. She never came back to visit, nor did my father invite her to remain in his life. This was to be my fate, as well; I just hadn’t seen it yet.

Despite our wounds, none of us are exempt from the results of our own behavior. I had my own portion of responsibility for having become so alienated. I replayed in my mind how selfish I had been. I questioned over and over again how it was that I had failed so miserably at securing my father’s love.

Why didn’t I work harder to fit in?

Why couldn’t I have been a better daughter?

I am an awful human being and no good will ever come of me. I tried so hard, but it’s no use. I am corrupt.

I felt powerless to fight against the doubts of my own worth; even my own father, for some reason, could not come to rescue me. I tried to soothe the savage voice inside me that urged me to put out the light and just give up. I didn’t really know what to make of the world after such a crushing blow, but I needed something to kill the pain of it.

BY MOST STANDARDS, I had always been a pretty good kid. I kept good grades, minded my curfew, and generally achieved all that was expected of me. While the other high school kids were out testing the boundaries of their coming adulthood with the usual suspects of sex, drugs, and alcohol, I usually preferred to keep distant from the riskier adventures. My pride came from my accomplishments in school and in music. I had looked forward to my own future enough that I didn’t care to challenge the odds of getting pregnant or dying in an alcohol-related car crash. There were times when I’d make my way to the clandestine parties that took place out by the river, have a couple of weak beers, then head home, but that was usually more than enough for me. Whenever I felt like I needed to blow off steam, I typically picked up my horn and let her rip, but as the gravity of my losses at home began to settle in, I was finding that I needed a stronger opiate to soothe my wounds.

In a lot of ways, I had always tried to be good for my dad, but I was starting to doubt the point of it. So far as I could see, the new gelding stood a better chance than I did of being cared for, so I decided to loosen up a little. Instead of spending my whole weekend delivering pizzas or breaking my face with trumpet practice, I decided to spend more time with my friends. Before I knew it, I’d be graduating and have to be a responsible adult without ever having had any fun.

It felt good to lose control. Come Saturday night, I’d head out with my friends to some dark, less traveled country road, park my car, and begin to tear through a flat of whatever beer we could afford. We’d let the alcohol take us through the paces. From the lip-tingling stages of getting buzzed to the syrupy world of unrestrained inebriation, I had finally found the trick to stop my mind from racing into darkness. I loved pushing through the alcoholic haze into the land of complete numbness. With enough booze, I could get to a place where I couldn’t even remember my own name or how to go back home. My mind would fail, along with my limbs, and all I had left to do was sit there, swimming in dark nothingness. What bliss it was to have finally found a way to express all the pain I was feeling inside.

I wanted to feel like that all the time. I started to think that I was pretty clever. I was the so-called good kid that no one suspected was actually bringing my grog along with me to school and drinking every day in class. I found that if I added just enough schnapps and vodka to my ever-present bottle of orange juice, few realized that I had a constant supply of my numbing agent.

I got to where I was drinking myself to sleep each night, hoping that I wouldn’t wake up the following morning in a home where I was not even noticed. When the alarm clock splintered through my head the next day, I’d go through the same motions as I had every other day. Drive to school, mix my cocktail out in my car in between classes, and nurse my woes through the day.

Just keep putting one buzzy foot in front of the other, I kept telling myself.

All the things that I had fueled my spirit with had seemed to lose their luster. I was struggling to see how music was going to get me out of my house, away from my parents, and out of my sleepy little town. I would grow sad when I would think of what my old friend Carol would have thought if she knew how low I had let myself sink, especially when it came time for my last performance at the Kansas All-State Band concert.

My senior year, I had won the first chair for trumpet again. After four years in a row, I was growing bored with the affair, not to mention that I failed to see the point of it when college now seemed improbable. Rather than spending the day aware of my surroundings, I did my now-usual routine, sipping my vodka-orange juice cocktail throughout the day’s rehearsal. When it came time for the evening’s performance, I suddenly realized just how drunk I was.

The lights flickered, the audience rustled in their seats, then the conductor took his place in front of the band. I looked over my horn, down to the sheet music in front of me where the black dotted notes swam across the page. I couldn’t make sense of any of it. I didn’t know how I was going to get through the performance.

The conductor raised his arms so quickly to start the piece that it left me feeling dizzy and seasick. The cymbals crashed. The band leapt into a march and there I was, stuck in the middle, trying to keep up.

I don’t remember what we played, really. I faked my way through most of the night. That I even sat through the performance at all seemed my best achievement of the hour. My fingers, lips, and brain were barely under my control. At some point in the evening, I had a few bars of solo to perform. It should have been a moment of supreme achievement. My senior year—a step-out solo as a state-honored musician, and I was blowing it. It was a moment in which I could have celebrated all that I had worked for in recent years, but I was so intoxicated, I don’t even remember how well I played it, or if I even played it at all.

It could have been a wake-up call, but it was just the beginning. Somehow, I managed to avoid anyone detecting the fact that I developed a serious drinking problem. No one seemed to notice, so I figured that I had a pretty good handle on things and kept on drinking. I relied on the alcohol to get me through every stressful occasion. It gave me the courage to get through what remained to be lived out in school—through prom night, through SATs, through the last of my high school concerts, until at last I called upon it to numb the pain of leaving my childhood home.

For all the years that I had spent dreaming of getting out and away from home and moving on to college, graduation day came with more of a thud than a sense of relief. As I sat and listened to my old band play countless rounds of “Pomp and Circumstance,” I waited for my name to be called so I could take the stage, have my tassel turned, grab my diploma, and walk off the stage into my new adult life. But, as I sat there, I realized that I was now officially adrift and alone.

While all the other students were greeted with loud pockets of cheers from their families in the audience, I walked up for my turn in relative silence. I scanned the crowd to see if my father had come, but he had not. I was devastated. I felt like I had reached a dead end rather than a new beginning. His absence confirmed that whatever I was to do now in life, it was going to be without his support.

That night, and for the several days that followed, I fell into an alcohol-induced abyss of self-pity. I spent my nights crashing on sofas or in the back seat of my car, convinced I had fallen down the wormhole of despair I deserved. I was s

tuck vacillating between complete rage and devastating suicidal depression. When I was high, I had the courage to be justifiably angry at my father’s lack of visible support. When I was hung over, I fought to keep from sliding into the suicidal depression that was overwhelming me. I was at a crossroads, trying to weigh the options of whether I wanted to continue living. The dreams that I had, the joys of music, the deep love I had for experiencing life were still floating around somewhere in the chaos of my mind, but they were at war with the darkness of having lost the sense that I mattered. The anger inside me won out. I didn’t have any earthly clue what I was going to do next, but I wasn’t going to give into the idea that I should just quit living.

In a moment of brief sobriety, I returned home, packed a bag of what little I thought I could not live without—my trumpet, my papers, and a few clothes. A part of me hoped for a sign of resistance, hoping that my unexpected departure would start a fiery family brawl to mark my last rite of passage. Instead, my father sat frozen and silent in his Laz-Y-Boy, as I gathered my things.

“I can’t live here anymore,” I said, resting my bag beside the back door. I waited for him to speak, but there was nothing. I needed to go, but I was afraid. Outside, a friend was waiting in the driveway to take me to wherever I wanted to go next, but I had no clue where that was going to be. I would have taken help if I had known how to ask for it, but all I could do was stand there wishing my imaginations into life.

I wanted my father to say, “Just stay for a little while longer so we can figure out what comes next.”

I stood next to him, frozen, waiting for a response. Unmoved, he sat with a stillness unlike any I had ever witnessed. I could hear the dogs barking outside. The mantle clock ticked away. I could hear him breathing. He took a deep intake of breath as if some kind of proper goodbye was about to escape his lips, but all that came out was a plaintive sigh.

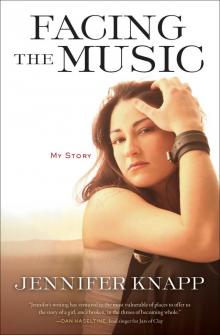

Facing the Music

Facing the Music