- Home

- Jennifer Knapp

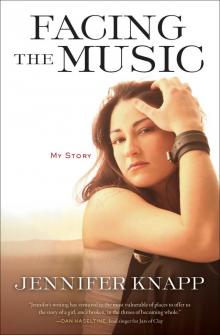

Facing the Music Page 13

Facing the Music Read online

Page 13

One day, in the chaos of an autograph line, a young, tomboyish girl pushed her way forward and handed me a CD to sign. With tears in her eyes, she leaned toward my ear and whispered, “I have to thank you. Your music has saved me from a life of homosexuality.” She seemed shaky and unconvinced, almost coerced.

I was gob smacked. This was far from what I had signed up for. I wanted to ask, “What on earth gave you the idea that I thought being gay was wrong?” But I said nothing to alter her course. I’d like to think that I gave her a resounding affirmation of whoever she felt herself to be, but I probably just offered a trite spiritual cliché, signed her CD, and moved on to the next person. Instead of hugging her and telling her that she was beautiful just the way she was, I kept my views to myself. I knew better. I kept my mouth closed and my fingers tightly wrapped around my Sharpie. I had read my Bible cover to cover, and again in multiple translations. I was aware that there were verses that didn’t look favorably on homosexuality. I had even been pulled to the side a time or two myself and rebuked for having the appearance of being gay—being judged to be too friendly with this girl or that. But, then again, that had happened with my male friends as well.

Still though, even after I had read the Bible, what seemed important was the heart of a person, anyway, not so much the body. While the body did matter in some part, everything that I read seemed to point to taking care with our bodies so as to reflect respect for our own physical person and that of others. Love, above all else, however, must rule, even if we debated about how to use the plumbing involved.

My church taught, and most people in CCM believed, that homosexuality was definitely a no-go. That I didn’t necessarily agree was a matter that I learned to keep to myself for fear of being labeled supposedly un-Christian. I didn’t want to unnecessarily rock the boat. It wasn’t until I met this young woman that I took into account what being a representative of that style of religion actually said about my own character and beliefs.

WALKING AWAY FROM the night, I replayed the incident over and again in my head. The encounter left me physically sick to my stomach and questioning whether I wanted to be associated with encouraging this kind of Christianity. My faith had been teaching me to be at peace with who I was, and to not be humiliated by imperfection. If anything, I had hoped that what I brought with my music was a sense of valuing ourselves just as we are presently found, accepting the grace that we must surely need in order to move forward in our journeys positively.

Foolishly, I thought I was doing an incredible job at subtly distancing myself from the fire and brimstone kinds of Christians that viewed gays as less than in the eyes of God, but clearly, I had not. She thought I was one of them and I had done nothing to tell her any differently.

It was one thing to hold a different theological position privately, but now I was being credited with supporting this potentially spiritually and psychologically damaging tradition. I could have stood up and taken responsibility for my part in this tragedy but, in my silence, I gave consent. Rather than take the risk of being compassionate, I chose to not inconvenience myself. I chose to protect my career first and hoped that the young woman could survive in a world that said it was wrong for her to be herself.

Egotistically, I was ashamed that she could have viewed me as the sort of person who would have such an idea. In a more global view, I was reeling at the thought that I was perpetuating such a limited brand of Christianity. I don’t know why it surprised me so much, when I knew that I was a part of a religion that had a history of calling such things a sin. I had in the back of my mind a vague recollection of Anita Bryant’s gay witch hunt through Kansas in the late seventies. I found it comical that Jerry Falwell’s favorite scapegoat for disastrous earthquakes was homosexuality and not a natural shifting of tectonic plates. The lunacy and demonization that they preached didn’t seem to add up with the gay people I had met in my own life.

I’d known a few girls who liked girls and boys who liked boys in college. I came from a small town, but there were a few gay folks there, too. I knew better than to speak of it, but there were a couple of times when I had felt drawn to kiss a girl friend or two myself. When I bothered to think of it, my own sexual experiences with men weren’t really all that appealing. As it was turning out, celibacy was a great safety net for my private, internal questioning.

Maybe, I wondered, human sexuality is a little more diverse than just being attracted to the opposite sex?

I learned to keep my thoughts to myself. I’d seen the effect of whispers behind the backs of my unmarried, middle-aged friends. I’d watched as my own Christian friends ostracized those whom they suspected to be gay.

In my own life, I found celibacy the best way to avoid any spiritual judgment regarding sex. After I became a Christian, I had experienced the harsh sting of having my natural hormones and sexual past pointed out as failure. There were times when my sexuality came into question, but I was eager to move past any shaming. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I handled any potential conflict by shutting down my entire sexual identity. To not have sex or talk about having sex was the best way I figured I could keep the peace. If I was to ever have sex again, it was a long way off. I had too much learning to do in figuring out how to be a good Christian woman first.

In meeting this young girl, I knew her pressure to conform both socially and spiritually, and, now, I was conscious that I was perpetuating a religious prejudice, thanks to my own silence.

That episode would be one of many in a growing stockpile of experiences that began to chip away at my faith. The pressure for me conform to a world that dictated what a Christian looked like, believed, and endorsed, was increasing. Everywhere I turned, I was either being praised for representing the conservative ideals of Christian culture by simply showing up and singing or I was being accused of being a charlatan for not supporting specific causes.

Eyebrows were raised and my faith questioned when I turned down the honor of having one of my songs used in support of a True Love Waits campaign. (This was the name given to a religious campaign that hoped to inspire teenagers to remain virgins until marriage.) In all honesty, I just couldn’t do it. It wasn’t my style, nor of any benefit, to my thinking, to tell a young girl that God loved virgins most. Whatever came out of my mouth, I wanted it to be: God loves you. Period.

The ironic thing was, though I didn’t necessarily want to be the kind of evangelical that led people in prayers to accept Jesus, I was truly moved to be an ambassador for the best parts of the joys I had experienced in becoming a Christian. For kids who had grown up in the church, I wanted to be the person who helped inspire them to keep exploring Christianity, even when it seemed the church made it seem as though they couldn’t measure up. I wanted to take away the stigma out of doubt for believers and skeptics alike. Sure, the church and its people could be challenging, but what was that compared to the joys of tapping into Divine Mystery? I truly believed that one of the reasons that I was defying odds (that I was alive and healthy, a role model for faith, and getting the opportunity to make a life out of the music that I loved so dearly) was that I could honor the very faith that made it all possible. To suggest that I failed that mission, or was motivated otherwise, was to strike at the very foundation at what gave my life meaning.

I could hardly believe it, when, in 1999, I got an invitation to spend a week on tour with Sarah McLachlan’s Lilith Fair. It’s not often that Christian artists are given much credence in mainstream environments, so I took it as a high compliment on both a personal and an artistic level. First, that the Lilith gang didn’t think I was so far gone in religious overtones that I would be a distraction to the proceedings, but even more so, it was flattering to be considered artistically worthy of being allowed to rub elbows with some of music’s most inspiring female artists. If I had any career at all as an artist, it was via the legacy of such artists as Sarah, The Indigo Girls, Sheryl Crow, and Chrissie Hynde.

From Emmy Lou Harris to Suzanne Vega, there’s not a chick on this planet who plays a guitar without being driven by their inspiration and talent.

I jumped at the chance to play a few stops on their tour and didn’t think twice about it.

As we chased the tour through Ohio and Michigan in a packed Ford Econoline, we happened upon a Christian radio station that was hosting a heated talk-show debate. I could hardly believe what I was hearing. The emcee was going on and on about how I had embarrassed the church by playing at Lilith Fair. By chance, I found myself eavesdropping on a conversation over the airwaves about how I was lacking true Christian character by engaging with a group where there were known lesbians performing, as well as certain alcohol and drug use. How, in my right mind, did I not have the decency to see that this was a crime to the Christian witness to play in such a place? Through his rabble-rousing, he gave the number of the station and encouraged listeners to call in to add their thoughts.

I grabbed my cell phone and called. To my surprise, the host picked up the phone directly.

“Hi. I’m Jennifer Knapp, the singer,” I didn’t expect him to believe me. “I thought maybe you’d like a chance to talk with me directly rather than postulating on why I’m playing Lilith?”

The other end was quiet for a moment. “Uh, really . . .? You’re the real Jennifer Knapp?”

I explained that I was in the van, cruising to the next show, and happened upon his lively one-sided debate. Rather than talking about me, maybe he’d like to talk with me instead, I challenged. Surprisingly, he put me on the air for the better part of the hour, peppering me with all manner of suppositions, the grandest and most presumptive of all being that good Christians don’t associate with the likes of what Lilith represents.

“Why wouldn’t I aspire to be excellent in my craft?” I asked. “I’m not changing the lyrics to any of my songs. I’ll be singing them as they were written. Why shouldn’t I celebrate wherever I get the chance?”

I am dubious that I changed his opinion of my exploits in any way. I recall we ended at an impasse. The chink in my armor had been found, however, and the criticism of my faith started pouring in from all sides. Bee in my bonnet, I wanted to answer them all, both in defense of my own integrity and for honest criticism of Christianity. For one short summer, I let it rip.

What on earth makes one Christian better than another? Aren’t we all on a spiritual journey together? I dared wonder aloud.

I was single, in my mid-twenties, and hanging out at Lilith Fair. Internet forums were filling up with accusations and judgments. Some speculated that I must be a lesbian, since I had yet to marry and had no children, so advanced in years as I was at twenty-five! Like a fool, I thought I could engage the crazy and make some kind of sense. At one point, I posted this response:

“I’ve never been arrested, shot up with heroin, and I’m not gay. (At least I assumed I was straight at the time.) Besides those things, the answer to anything you could possibly accuse me of is yes. So what then? Does my faith mean nothing? And what if I were or had done any one thing that you think makes my experience with God invalid? Who of any of us gets to decide or judge? I am doing my very best, beyond that, it’s your choice to listen to my music or not.”

It was so dispiriting to have to continually defend the value of my faith and the methodology and places where I chose to share it. To me, Christianity was more than a lifestyle club, where all the good kids wore WWJD (What Would Jesus Do?) bracelets and sang only Christian music. Beyond the culture, there was an opportunity to discover inner peace and divine consideration. Yet, with increasing regularity, I seemed to be running into Christians devaluing the path of the journeyman.

Every day, I met young, beautiful, and inspired people who, like me, tripped along in their faith until they were disillusioned and fearing moral failure rather than living in the freedom that their faith promised. Whether I was tucked into a dark corner on campus at Liberty University digging into the confounding questions of Christianity with an eager student or consoling a teenager who had just been kicked out of her youth group for having sex, I couldn’t bring myself to believe that we were all engaged in a pass/fail religion. I couldn’t stomach the thought of witnessing yet another teen evangelical event where the raging sex drives of teenagers were held up as evidence of evil. I didn’t want my music to be the backdrop to this kind of insanity. Everything seemed to be about what you looked like, while in the background, we were all living double lives. We’d put on our best faces for the crowds, sing our ditties, go to church on Sunday morning, then drive twenty miles away to nurse our sorrows in a thirst-quenching beer, while we tried to reason our way out of being complicit in whatever we were a part of.

These were the thoughts that occupied my mind as tour after tour passed. In 2000, I recorded my sophomore record Lay It Down. I let my growing frustrations out in the title track.

Seeing as I found a rock in my pocket.

Seeing as I found a glitch in my soul.

Make-believe won’t hide the truth

When judgment falls, it falls on you

Bend a knee my friend, bend a knee . . .

Lay it down, say it’s “all my fault”

Say, “I believe! I believe!”

Lay it down.

It’s the hour of my healing.

—“Lay It Down,” Lay It Down (2000)

I wrote about the forgiveness I knew I had experienced and the building pressures of having to defend that faith. Many understood that defense of faith as being sung to an un-Christian world, but I was singing it to Christians. The sophomore release got a Grammy nomination and was said to have been critically acclaimed, which is to say that it didn’t sell as well as some thought it should have, but a lot of people had heard enough of it to be critical. It “only” sold 250,000 copies. It was a disappointment at the time, considering Kansas would go on to sell more than twice that.

Professionally, I had no right to complain. I had success and could bank on it more than most. Still, I found myself pushing through an inner turmoil no amount of professional success could quiet. The way I saw it, I had worked so hard, pushed past my introverted nature and into the outside world so that I could engage with those who embraced the mystery of grace.

I was still in the middle of touring Lay It Down when Gotee came calling for another record. I needed to take time to process the spiritual quandaries I was facing, but instead I wrestled them in dark, lonely dressing rooms in between shows.

Gotee wanted a record and I barely cared. I was tired. I struggled to find joy in my faith. All I could see was an endless uphill climb.

The only thing I knew how to do was confront the conflict growing within me.

In sitting down to write the songs for The Way I Am, I decided to go back to the story of the Jesus that started it all. I wanted, desperately, to return to the wellspring of my adventure. I needed reminding that my faith was more than a religious cult, but practical, relevant, and not just for the elect few.

Whether anyone liked it or not, I was growing up, graduating from the religion that I had been handed, and wrestling with the reality of what being a Christian was going to mean for my life in the long term. I looked to the Passion of the Cross, the flesh and blood, the humanized body that took the punishment for all our sins, and used that as inspiration for my third record The Way I Am.

I took my frustration and put it into what I thought was obvious satire. I wanted to paint a picture of what humanity remained if we literally did as the Bible implored—to pluck out every sinful eye, cut off every thieving hand.

Blind these eyes who never tried to lose temptation

I’m so scared, where’s the hesitation?

You so easily proved that you could save a man,

Well I am that man.

It’s better off this way, to be deaf, dumb and lame

Than to

be the Way I Am

It’s better off this way, to be searching for the grave

Than to be the way I am.

PRETTY GRIM STUFF, considering the saccharine cheer from the standard CCM offerings. It was meant to lead to an aha moment, to consider grace when we are a little less than perfect, to insist that we are all still worthy of being loved, as we were found by God. That to go to the extremes of punishing ourselves was more damaging than it was fruitful. More limited than freeing. That we missed so much of the good, destroying any hope of the future, by cutting ourselves off for one sin, one flaw, one weakness, at the expense of the full measure of life in front of us.

One night, I shared my growing frustration with my audience. “If I chopped off every part of my body that has ever caused offense, there would be nothing left of me. Nothing!” Some shook their heads in sympathy, but most seemed annoyed that I was talking.

When I pushed the audience in front of me to contemplate their faith and not just dance to it, all that came back was confusion. “I thought the point of all this was that none of us were without fault. We’re all in this together. ‘That while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us.’ Isn’t that what it says?”

The response was an entertainer’s worst nightmare . . . silence. There were two thousand people in front of me, and there wasn’t even a teenage girl giggling about boys in the distance.

I was missing the connective thread that allowed others to join in my wandering, but had no strength left to find it. I felt hung out to dry and alone, an alien in a world that I had never fully ceased to test. Night after night, I failed to find community through the music that had so often supplied it. Maybe, I wondered, I’m not really family after all?

This wasn’t like the early days of my faith, when I had the cover of anonymity to guard my personal odyssey. The demands of my career afforded me little privacy and rest to hash out my troubles in solitude. My internal thermostat was reaching a boiling point and I knew it. I needed to get off the road, recuperate, and try to make sense of all that was swimming in my head, but the train was going at full speed, showing no signs of stopping. I was a business now. If my person wasn’t working, nobody in my camp was making money. And that was a big problem.

Facing the Music

Facing the Music