- Home

- Jennifer Knapp

Facing the Music Page 14

Facing the Music Read online

Page 14

One day, in exasperation, my defeat tumbled out onto the public stage. In my usually uplifting between-song banter, I wondered aloud, “If I need to be theologically perfect with whatever it is everyone thinks makes a Christian a Christian, maybe I am lost?”

Nothing. Silence. Blank white-faced stares blinked back at me.

After that, I honestly felt like I had nothing left to contribute to the scene. I didn’t want to stand in the crowd and feel so alone anymore. I didn’t want to cause other people to doubt their faith. I didn’t want . . . a lot of things. That day, I decided I needed out.

fourteen

The irony of my career as a Christian music artist was that I had a passion for the stage and, at the same time, always struggled to see myself as destined for it. Perhaps it was because the vision to perform Christian music had not been initiated from my own desire?

From the moment I had become a Christian, it seemed there was always a believer encouraging me to view what talents I had through the lens of God’s anointing. Such things, at the start, didn’t necessarily mirror my way of thinking. I had been, and continue to be, thankful for the gift of music, yet the idea that I was given that gift by God for the sole purpose of serving the church for the rest of my life was a seed that had to be planted and nurtured by others.

It was Ami who introduced me to the idea of channeling my faith experience into music. It was Byron who laid the groundwork for my burgeoning career. My home church was full of prayer warriors, leaders, and mentors who backed my every step, convinced that I was in the center of God’s good will for my life, while I did my best not to squirm too much. I loved being on the stage, I loved connecting with people, and talking about my faith, but I seemed to always be getting pushed uphill by something other than my own ambitions.

Byron and I had parted ways early in my professional career. He had been a good friend and mentor, but we never fully came to agreement on the mission statement my career was to have. He had a mindset for intimate, hands-on work in and amongst those I was called to perform with, while I was more comfortable keeping my zone of responsibility strictly within the boundaries of the stage. Byron and I parted ways when I signed on with Gotee, and I found a new manager to fill his shoes.

I was fortunate that, while Byron had kept me focused and motivated on a life serving the church, my new manager Steve quickly stepped in to bring me up to speed on life inside CCM. A Christian with his own history of working inside Christian culture, he shared my own idea to serve the church well, but also understood the nuances of making a profession in a faith-based industry. Together, we shared an understanding that some artists were simply meant to be artists and not ministers. We agreed that musicians were called, at times, to be the mirror of experience. We hoped that, rather than solely being exemplars of the homogenized Christian lifestyle, there could be a place reserved for artists in CCM to present the diversity of the lived Christian experience. So, around 1998, Steve and I bypassed a standard manager/artist agreement, and instead established our jointly owned artist management agency, Alabaster Arts.

Our hope for Alabaster was to professionally manage, support, and mentor Christian artists who were culturally relevant both in, and apart from, the church. For my part, I wanted to help artists professionally navigate the CCM industry while encouraging them to be artistically daring in expressing their true faith experience. Within a few years of setting up camp in Nashville, we began managing CCM veterans like The OC Supertones, newbies Relient K, as well as a few never-before-heard-of artists whom we would work to break out.

Part of setting up a management company was so that I had a job after I had had my day in the spotlight. While I loved my own work out on the road, I didn’t see myself being on the road forever. The work was tiring, with little chance for rest, as well as being philosophically grinding. I was fortunate throughout my career to have fans, a label, and management that supported my efforts to be honest about my faith experience. Yet, for what it cost me in personal energy, the results coming out of the other side of the sausage factory seemed to be a rendered-down version of what I had imagined. There was no way I was going to be able to keep doing this forever, and I had known it since the beginning.

My plan in establishing and investing my experience and financial resources into Alabaster Arts was to continue with the passion that I had to affect Christian culture while not having it come directly out of my backside.

I never kept my intention of leaving the public eye a secret. I was quick to remind those closest to me that I didn’t imagine that I would be acting out my role as a performer for the rest of my days. I had often had conversations with Joey Elwood, Gotee Record’s president, about how I was putting every ounce of my heart into what I was being called to do, but that I did not hope to make a life of this particular kind of work.

Alabaster Arts was my distant finish line. My touring schedule and album releases had my body committed to being a Christian rock star for the next two years, while I filled my energy reserves to survive it with the dream of retiring behind the scenes to be a mentor.

My rigorous schedule had its benefits. The money I was earning as a performer went primarily into Alabaster Arts. I completely expected that this would eventually lead to my own job security, and preserve the opportunity to do work that was personally meaningful. Things were going well. We employed a handful of full-time staff, signed a range of veteran and developing artists, and had even extended into buying a small booking agency to build our empire.

From the time I had signed on with Gotee records and made my commitment to being a professional artist, every waking minute of every day had been all about my career. If I wasn’t in the studio, I was on a bus. If I wasn’t on a bus, I was on stage. If not there, I was tucked into a dingy dressing room somewhere trying to write more music for the next record. On and on it went.

I was so busy that, when I moved to Nashville in 1999, I had to hire a moving company to make it happen. I had to let strangers touch and pack every single thing that I owned into boxes, shove them on a semi, and trust that I’d have a home to go to when I walked off the tour bus.

I bought a modest home in the quiet, rolling hills, thirty minutes west of Nashville, in a little hamlet called Kingston Springs. I had walked through it once, maybe twice, signed the papers, then got back to touring. It took over a year to unpack the few boxes I had, as all I really needed was already on the road with me.

To the outside world, this was success. I had gigs booked, money rolling in, and record sales as far as the eye could see. My career was flourishing but, inside, I was growing weary.

There were no boundaries between my life and my career. They had merged to the point that my body was merely the host for industry. It didn’t matter that inside my little body was a person who needed a vacation. The body that I inhabited had a business to run. Gotee relied upon it, concert promoters had tickets to sell, and Alabaster Arts had mouths to feed. My career didn’t feel like it belonged to me so much as I belonged to it.

I had spent the better part of 2000 requesting that Steve devise a plan to get me off the treadmill for a while. My sophomore release, Lay It Down, had done very well. I’d shared a fruitful tour with CCM rockers Third Day. The record received a Grammy nomination, and had several radio hits. There was no question that I had a long future ahead of me in CCM if I wanted it.

“We’ve worked really hard and things have gone well, but if I don’t get a break soon, I’m gonna lose it,” I would say. Every chance I got I steered the conversation to easing up on the throttle, “You gotta stop booking shows and give me some time off.”

“WE GOTTA STRIKE while the iron’s hot,” Steve would counter. His fear was that if you weren’t in the spotlight, you were out. It was a risk I was willing to take, but Steve insisted, “If only you could push on just a little further, one more record, drive on for a while more . . . Just one more tour and A

labaster will have an office ready and waiting for you.”

I found myself trapped in a cycle that seemed unending. Every time I would agree to one more push, the finish line kept moving one more step further. When was it going to stop? When was Alabaster going to be prepared for my retirement?

I was losing my grip out on the road, getting more and more agitated. I was a shell of a human being, walking about in a coma, mindlessly doing what was scheduled for my body, but completely empty in spirit; all I could think of was not being obligated to work one minute longer. For every minute that passed, it felt like a march against my own will.

To cope, I’d lock myself in the bus for hours on end, unable to find the energy to overcome my introverted nature. Even trips to sound check and back could zap what little conversational energies I had squirreled away.

Keeping enough energy to get through a night’s performance was daunting enough, without having to run the crucible of Christian kids that were scattered in the hallways between the bus and the stage. It got to where I truly hated the sight of anyone who might be trolling for a backstage autograph. Something was very wrong inside me.

Normally I loved my fans. I loved them so much that I hated calling them fans. It belied the fact that I had always been so honored by their support and was always glad to spend as much time as humanly possible saying, “Thanks.” But now the sight of a bright eager face sent chills down my spine.

“Miss Knapp! Miss Knapp!”

I saw a young, pretty college girl coming down a backstage corridor toward me. Jesus, I thought to myself, why can’t people just leave me alone? A person would have to have been blind and deaf to not notice her, but I tried to get away with ignoring her.

Undaunted, she followed me down the hall, “Miss Knapp! Miss Knapp?”

“Who let you in here?” I turned and questioned with obvious disdain.

Caught off guard, her cheery face paled from the shock. “I—I . . .”

“What can I help you with?” I interrupted, pushing for her to get on with it.

“I only wanted to say ‘Hi’.” She mumbled, her chin dipping into her chest. She managed to go on, despite my ungracious demeanor, “Your music has meant a lot to me . . .” her words trailed off, unwilling to say anything more. She made herself vulnerable, sharing her appreciation to a stranger, only to be treated with ambivalence.

I gave her an autograph and said, “Thanks,” but little more. I went back to the dressing room and cried from shame.

From 1999 until I would call it quits in 2002, things would move so fast, I would work almost nonstop, that I would call them my “heroin years” as I found that trying to remember the specifics of those years so hazy. If I want to remember what I did in any given year, I search Google instead of trusting my own memory. If I want to remember what was going on in my life during that time I have to use my discography and tours as a guide to my own and world events. And, still, what comes back is a loose recollection.

Despite my pleading with Steve for more than a year, demands on me seemed to only increase rather than decrease. I was not only plugging away on the road, now I had the growing needs of Alabaster Arts calling as well.

We had signed a talented and raw new artist, whom we hoped to develop, in a young girl from California named Katy Hudson. She was seventeen years old when her eager Christian parents brought her to us, hoping that we could help her have a career similar to my own. They wanted her to sing Christian songs on a Christian label, and had come to us to help her make it possible. Katy definitely had the it factor, she just needed a plan. She had a femininely styled Taylor guitar, a decent set of songs she had written, and a great voice, and it was exciting to watch her perform. She was young and unpolished for sure, but she had a huge, fresh voice, and seemed bound for the stage with a little direction.

In house, the idea was to put her out on the road with me, so that I could act as a sort of mentor. In theory, it was a great idea to give Katy some experience in touring but, by this time, I was hardly fit to be, nor selfless enough to be, a proper mentor. I was threadbare and the last example of Christian female artist virtue she needed to see. I was barely getting by, bitter, and in need of rest. In my role as manager, I was excited to help her on her journey, but out on the road I was cracking up. I hardly thought it was a good idea to send a minor out on tour with a supposed mentor who was in such a poor psychological and spiritual state. I barely had the integrity to take care of myself, let alone be trusted to be the chaperone of a beautiful, busty, flirtatious teenager.

Nonetheless, onto my tour bus she came. I took a run of shows in the Northeast, through New York City, then up to an exclusive youth retreat in New England. The idea was to give Katy an insight into the breadth of the kind of gigs that she might experience as a Christian artist at Alabaster. Some of the shows would have a secular feel, while others would be in a more intimate Christian setting. The whole thing was a disaster.

I had landed a gig at the storied Mercury Lounge in New York. The band and I were all excited to have a show away from the stuffy church scene, where we could have a few beers, relax, and put on a rock show free from the obligations to push Jesus. I was starting to get more shows that suited my desire to perform music as a so-called normal artist, and was making an effort to build my credibility as a marketable artist beyond the CCM scene. The following day we were taking a less desirable role as entertainment for a youth retreat, but today we were celebrating what felt like a hope for the future. Katy opened the show.

Steve came to Manhattan, as well, to talk with some contacts about expanding my career beyond CCM. After the show I joined him to wheel and deal for a bit, but quickly found myself angered by his approach. When all I could do was think about the rest I needed in the near future, he was trying to make more immediate plans for work. My input was causing the conversation to deteriorate to the point where he pulled me aside, gave me what for, and asked that I go back to the bus to babysit Katy. I was angry for that and let him have it. I erupted in a tirade of abuse. It became clear that I had reached my breaking point. Yes, I was encouraged by the thought of performing outside of CCM, but I needed him to stop pushing so hard. He told me that I needed to “get right with God” and I told him to go f#@k himself.

I went back to the bus, told Katy to stay there like a good pet, left her some food and water, then took off to whatever bar my band was hanging out in.

I wasn’t alone in my low Christian morale. All of us in the band were struggling. Years later, when we would reconnect, many of us would confess to one another the turmoil we felt in ourselves. We were serious about our faith, yet we were also aware that we didn’t want to act out the prescribed model of what we were supposed to be. That night, we drank heavily in our rebellion.

It was scary. Harkening back to my old ways of drunken debauchery, I tied it on like it was my last night of freedom. I let my despair pour freely from my mouth and chased it with more shots of tequila than my little body could handle. I garnished my night with salt and lime, forgetting about all my responsibilities. Screw CCM. F#@k Steve. I wanted no further part of any of it.

In the wee hours of the morning we all managed to make our way back to the bus, only to realize that innocent little Katy would be there. I slurred my instructions to the crew to get themselves together so that we might not be accused of being the disastrous Christian witness to Katy that we most unavoidably were.

Fortunately, Katy was safely where I had left her, and she greeted us with her usual perky personality. “Hey guys! Where ya been?”

One by one, we wafted past her in a haze of smoke and booze and tried to pass off just how irresponsibly drunk we all were. I thought we were all making a pretty good show of it until our old Senator tour bus reached the mountains of New Hampshire, or wherever it was were headed. Our driver laughed and did his best to keep the bus from pitching and rolling through the night, but one b

y one, we succumbed to inevitable seasickness. One bathroom, nearly a dozen drunk riders, all trapped in a rolling metal washtub. The idea that we put anything over on Katy was laughable. I was mortified at how I had behaved and had nowhere to hide my shame.

The next morning, our bus was parked in the heart of a Christian kid’s camp. Our trusty road manager peeled herself out of bed and tried to keep a quiet perimeter around the coach so we could sleep off the previous night’s bender. The excited campers had been looking forward to the idea of taking us horseback riding, swimming at the lake, and integrating us into one of their many afternoon Bible study sessions, but I was hardly fit for public consumption. Hung over and thoroughly ill, we barely managed to make the stage for sound checks that night. I didn’t care what the fallout was. I didn’t care how much saving and planning that camp had to do to get us there. We played our show. Picked up the check. I had done my job, but had little concern for much else.

This was not who I wanted to be.

At that point, I didn’t know who or what I perceived I was failing, but I wasn’t happy. I was depressed. I recognized it, but I had to stop the machine to get my bearings.

I went to Steve, to Joey at Gotee. I told everyone within earshot that I needed a break. I had decided that enough was enough and that my schedule was not going to extend one single booking beyond what was already there. At every interview, I conveyed my message: I wasn’t going to be here much longer. I had hinted at such ideas before, but now my aim was clear. I was done.

Steve accused me of having a breakdown. Maybe I was having one, but with good reason, which should have prompted him to take my cries for a reprieve seriously. Instead, he pushed for me to get my head on straight and get back to work. Work was the last thing I needed. I needed rest.

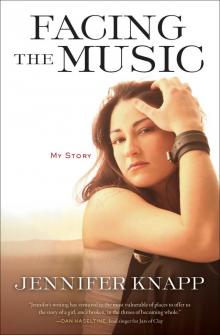

Facing the Music

Facing the Music